Bot Control for Horses

How well does your bot control check out?

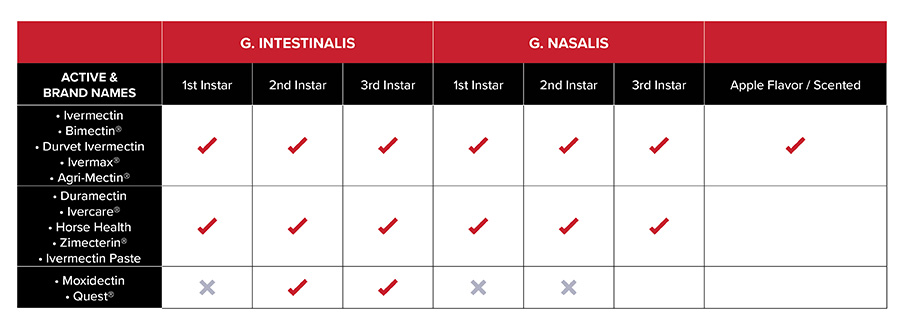

Today’s equine dewormers are not all created equal

Related pages

.jpg)

How well does your bot control check out?

Today’s equine dewormers are not all created equal.

* Dewormers containing the following active ingredients have NO boticide control: fenbendazole, oxibendazole, pyrantel pamoate, pyrantel tartrate. Per FDA label and FOI summaries

Quick bits

When should I deworm for bot control?

Typically fall, August through December, pending weather conditions. Bot infections start with flies; when fly season stops, eggs stop being laid (see life cycle). In areas with heavy fly populations and a long summer, some horse owners may need to deworm early and late fall.

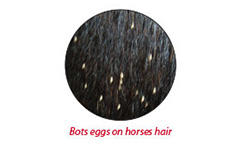

Can you tell by looking if your horse has been infected with bot larvae?

Most likely no, but many horse owners will see eggs on their horse’s legs, chest, etc. This is a good indicator you definitely want to deworm with a product labeled for bot control. Don’t rely on seeing them alone; eggs can be laid and ingested without being visible.

How damaging are bots?

Bot flies have a unique life cycle. They can cause damage to a horse in two locations, the mouth and the stomach. The larvae cause damage as they migrate through the horse’s system, from the mouth to the stomach. Damage can cause chronic and short-term issues (see life cycle).

Does fecal testing detect bot larvae?

No, bot larvae rarely show up in fecal tests.

Can I control bots naturally?

You can help minimize bot infestations by removing visible bot eggs (scraping or washing off), but a treatment with an FDA-approved boticide is still needed.

Are there flavored bot control products?

Yes, Ivermax® is apple flavored and scented.

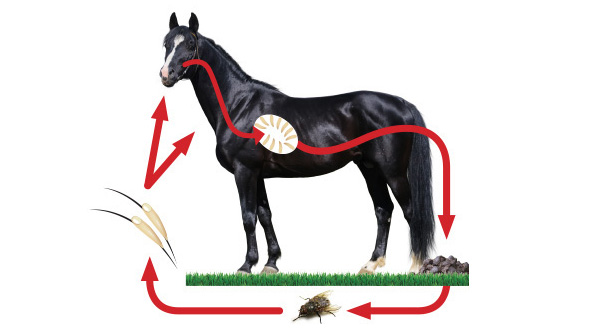

Life cycle of the bot fly

Adult bot flies are brown, hairy and bee-like, with one pair of wings, and measure about 3/4". In the summer months, adult bot flies are a common sight around horses. Yet this adult stage is just a brief part of the bot fly life cycle. Female bot flies have no mouth parts, so they cannot feed. They live on stored reserves only long enough to lay eggs on the hair around a horse’s eyes, mouth, nose, or on the legs. Moisture from the skin or from the horse’s licking causes the eggs to hatch into larvae.

The bot life cycle

After a three-week developmental period in the mouth, bot fly larvae of both species, Gasterophilus intestinalis and Gasterophilus nasalis, migrate and attach themselves to the mucus lining of the horse’s stomach and remain there during the winter.

After about 10 months, they detach from the lining and are passed out of the body through the feces. The larvae burrow into the ground and mature.

Depending on the conditions, adults emerge in three to 10 weeks. Adult females deposit eggs on the horse’s legs, shoulders, chin, throat and lips. Depending on geographic location, the life cycle of bot flies is not fixed to only certain times of the year, and bot larvae can be active in horses anywhere from August to May.

Learn to spot bot eggs

Egg laying begins in early summer

G. intestinalis lays up to 1,000 pale-yellow eggs on the horse’s forelegs and shoulders. Moisture and friction from the horse’s licking itself cause the eggs to hatch in about seven days. After hatching, G. intestinalis larvae are licked into the mouth.

G. nasalis lays about 500 yellow eggs around the chin and throat of the horse. These eggs are not dependent on the horse’s licking them to hatch. G. nasalis burrows under the skin to the mouth, wandering through it for about a month before migrating to the stomach for overwintering. Then the cycle begins again.

The bot: More than a pest

Signs of bot infestation

Horses that show no outward signs of illness can be severely infested, giving no clue to damage occurring inside. However, some horses do show signs of infestation, including an inflamed mouth area and stomach irritation. Infestation with bot larvae may cause ulcers in the stomach lining. If the infestation is severe, the opening from the stomach to the intestines may be blocked, which can cause irritation, ulcers and even colic. The burrowing larvae can cause small tears in the skin, which can become infected.

Treatment for bots

- Keep an eye out for bot eggs on your horse’s coat (typically the legs and chest area). If you see eggs, use a bot knife to remove them. This will reduce the amount of bots the horse ingests.

- In addition, horses are traditionally treated for bots in the fall, after a frost that kills the adult flies laying eggs. A product containing ivermectin is the most recommended treatment. Beyond its unsurpassed bot control, ivermectin is a great treatment to handle any remaining summer parasites and related conditions. In areas with heavy bot problems, additional review for deworming may be appropriate in the late summer/early fall time as well. Parasite control needs can vary by farms and within farms. Consult your veterinarian for assistance in the diagnosis, treatment, and control of parasitism.

Explore our horse dewormers

Consult your veterinarian for assistance in the diagnosis, treatment, and control of parasitism. Do not use in horses intended for human consumption. Not for use in humans. Keep this and all drugs out of reach of children. Equine anthelmintics containing ivermectin or moxidectin have been formulated specifically for use in horses and ponies only. These products should not be used in other animal species as severe adverse reactions, including fatalities in dogs, may result. Trademarks belong to their respective owners.

* Bimectin® is a registered trademark of BIMEDA Animal Health Limited. Ivermax® is a registered trademark of Aspen Veterinary Resources. Agri-Mectin® is a registered trademark of Huvepharma Inc. Ivercare® is a registered trademark of Farnam Companies Inc. Zimecterin® is a registered trademark of Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health France. Quest® is a registered trademark of Zoetis Services LLC.